MOLDOVA |

8 SEPTEMBER

The Minnesota Wife-Seeker

ODESSA I had to take the 07:50 flight and planned to get up at 4:45am. Instead of simply setting my alarm, I had somehow changed my watch timing an hour ahead as well. Hence, I ended up getting up at glorious 3:45am, washed up, and rushed downstairs to check out of the hotel. I passed the keys to the reception and ordered a taxi. A lady of evening pleasures sat lonely at the lobby sofa. Oversized bosoms seemed about to burst free above the line of her silky bright red dress. She turned her head, saw me and gave a faint smile. A hint of sales promotion. A brief eye contact.

“Taxi here,” the receptionist interrupted the ritual. Putting on my backpack, I clenched my fist. It’s time to go. I hopped onto the taxi, leaving Natasha in the cold, customerless lobby.

The airport was dead quiet when I arrived at 4:30am, thinking that it was 5:30am. There weren’t anyone around and the terminal building was firmly locked as well. So I had to stay in the freezing cold waiting for the next hour. When a watchman arrived to open the door, I thought, that’s slightly more than an hour away before the flight, and no service staff or passenger have arrived… what an easy-going place. It wasn’t until later that I realized how silly I was… an hour of sleep lost due to the screw-up.

Waiting for a flight at a strange foreign airport with few passengers can be an extremely boring thing, especially so when you have planned to arrive early on precaution and have actually arrived an hour before that by mistake. That was why I was relieved to meet Bill, the wife-seeker from Minnesota.

Bill, forty, tall chap with blondish head and a goatie, is an administrative officer at a second hand car company in Minneapolis. Or at least he claimed he was. He looked more like a second hand car salesman. He said he’s glad to meet someone who speaks “proper English.” He’s sick of what he called “materialistic feminist money-grabbing babes of America”, and is coming here to find the “real” woman, whatever that means. How did he get to know the women ? Through the internet. FSU matchmaking agencies on the internet.

The fall of the USSR and subsequent economic collapse of the successor states coincided with the advent of the internet. For a few decades, less eligible Western men sought refuge from mail order brides from countries like Thailand and the Philippines. The new political and economic landscape in the FSU suddenly meant the availability of thousands of white women who are culturally more compatible to these Westerners. Matchmaking agencies sprung up in every corner of the FSU, many with “photobook” internet sites. Both parties even become electronic penpals of sorts. That’s how Bill got to know Svetlana, the long-haired girl with a mole on her lower-lip who was sending him off, and other ladies he has been meeting in Odessa.

When Svetlana left for the toilet, Bill whispered to me, “I’m getting tired of her. I think we are not compatible at all. I should have tried harder to meet other girls. You know, Ukraine has the most beautiful gals in the world.” He smiled in a most lustrous manner. “She spent the night with me. This morning after we woke up, she cried. She said I must return again. But I just can’t see how I could do that. But of course she doesn’t know that.”

It is market of demand and supply. Foreign men have the cash and the right passport. Local girls are desperate to leave for a better life or to support a family in need, although whether those who succeeded in marrying a foreign man eventually achieve such goals is highly debatable. Often, the foreign man is less educated and physically less attractive than the FSU female on “offer”. A recent British documentary showed a farmer and a factory worker dating Russian doctors and university lecturers.

It’s the second time Bill has come to Ukraine. The first was five months ago, when he met, in his words, many “beautiful babes”. He thought he liked Svetlana, loved the country, friendly people and great climate. And so he came again in Summer. Now, he found the visa procedures complicated, Svetlana less attractive, the food’s bad, people rude, and the summer heat oppressive. Worst of all, he missed the return flight the day before. He had been waiting for the flight but did not recognise the boarding announcement, which was in Ukrainian and Russian. He had tried to keep his air fare low by booking a terribly bizarre combination of flights: Odessa – Chisinau – Vienna on Air Moldova International; Vienna – Frankfurt on Lufthansa; Frankfurt – New York – Minneapolis on United Airlines. With the missed flight, his Gordion-Knottish arrangement unraveled and he had to fly direct to Frankfurt from Chisinau, on a new ticket, or wait three days for the next flight to Vienna. Hence, instead of keeping costs low, his expenditure has ballooned. He’s also late for work, and any later, he said, he will be fired. Bill is now an angry man.

Svetlana has just returned from the toilet. Bill placed his right arm around her and then ran his hairy hand across her back. Svetlana turned her head and gazed into his oily face. She reached out for his goatie beard, stroked it gently. He smiled, and whispered softly into her ears.

The flight was now ready for boarding. Bill kissed her goodbye, and entered the passport control area with me. “Good riddance,” he said. I pitied Svetlana, who was now waving at Bill from the other side of the glass screen, her eyes melting with gentle tears. Bill waved back. “Free at last,” he said.

The customs officer ran his hand through my luggage and spent a few moments pondering whether my Lithuanian souvenir wind-bell – that sort you hang up in the house and rings when it is blown – was an antique. He asked to see my money as well. He counted the cash in my wallet to make sure there weren’t more money than the amount declared when I entered the country. He didn’t know I had more in my underpants, but I didn’t intend to do a full monty at the airport anyway.

I walked to the plane – a smallish YAK 40. It said Air Odessa

outside. I asked the crew whether this was the Air Moldova International

flight to Chisinau. “Same. Same. Nyet Problem.” Perhaps

they have a code-sharing agreement. These days you never quite knew

which airline you’ve booked, but Air Odessa was as good as AMI could be,

as far as I was concerned. I just wanted to make sure I was flying to the

right place. Minsk lesson learnt. There were 12 passengers

on this 27-seater plane. I touched my Guanyin talisman gently, and

off we took off for Chisinau.

We May Have To Depot You

CHISINAU

It was a short flight of about an hour. Actually, it wasn’t necessary

to fly given the distance. Regular buses take four hours to do the

journey. However, tiny Moldova has few embassies round the world.

None in the UK, and I was advised that I could obtain the visa upon arrival

if I book my accommodation in advance and present a letter of invitation

at the airport. I contacted a travel agency in Chisinau called EcoTurNova

via the internet and they were willing to make the arrangements for me.

Some say I could simply take a bus from Odessa into Moldova without being

checked. That’s because the bus would pass through the breakaway

Transdniestria Moldavian Republic, which doesn’t require any paperwork,

and Moldovan soldiers on the Moldova-Trandnestrian ceasefire line wouldn’t

check for the visa as that is tantamount to, god forbid, recognising that

frontier. I wouldn’t dare risk this, however, as foreigners like

me do get stopped by police on the streets and checked.

CHISINAU

It was a short flight of about an hour. Actually, it wasn’t necessary

to fly given the distance. Regular buses take four hours to do the

journey. However, tiny Moldova has few embassies round the world.

None in the UK, and I was advised that I could obtain the visa upon arrival

if I book my accommodation in advance and present a letter of invitation

at the airport. I contacted a travel agency in Chisinau called EcoTurNova

via the internet and they were willing to make the arrangements for me.

Some say I could simply take a bus from Odessa into Moldova without being

checked. That’s because the bus would pass through the breakaway

Transdniestria Moldavian Republic, which doesn’t require any paperwork,

and Moldovan soldiers on the Moldova-Trandnestrian ceasefire line wouldn’t

check for the visa as that is tantamount to, god forbid, recognising that

frontier. I wouldn’t dare risk this, however, as foreigners like

me do get stopped by police on the streets and checked.

Lush green fields came on sight as the plane began to land on this misty day. As I stepped out of the plane onto the runway, I got the feeling the place seemed to be covered with a strange smell – that of rotting vegetation and moldy paint-work. The Moldovan flag – basically the Romanian tricolour with the crest of Stefan cel Mare (Stephen the Great)’s Bull (together with Dacian symbols of the moon and the star) fluttered in the sky.

Almost all the passengers were on transit to elsewhere in Europe – who

wants to go to Moldova anyway ? Not that it isn’t worth going, but

there is simply too little publicity about the country. I walked

to the passport control telling them I am visiting Moldova. They

were taken aback, as the airline had told them all passengers were on transit.

My luggage was also held at the transit area. They mobilised an Air

Moldova International employee to deal with me. Maria, a black eye

Latin beauty in her twenties, chided me politely, “Why didn’t you tell

say you were not on transit ?”

|

|

|

|

|

Apparently, they had made an announcement asking those not on transit to go through a different set of controls. But Russian was as much Greek or Navajo Indian to me, and I wouldn’t have understood the instructions. First, they had to locate my bag, which wasn’t a problem, and then, Maria tried to contact the consul who, in her words, “will decide whether to depot me”, since I did not have a visa upon arrival.

“Hey, wait a minute, I have a letter of invitation and confirmed accommodation. The travel agent is probably waiting for me outside.” I insisted.

“OK, OK, we’ll see.” Maria was patient – a rare virtue in a region full of pompous bureaucrats and impatient nuts – and went through my documents diligently. She asked me to wait at the transit area while waiting the consul for further instructions. I sat there at the transit bar – Bill was there as well, waiting for the connecting flight to Frankfurt. I updated him about my latest adventure, but he was more keen on telling me more about his wife-seeking chronicles.

“I did managed to get in touch with a Chisinau gal before my first trip to Odessa, but she wasn’t able to come to Odessa to meet me. I should have considered meeting her here instead. Oh, I might have her number here. Perhaps I should try calling her.” Bill did a quick flip-through of his organiser. “A pity. I must have left it at home.”

The consul, a sleepy bespectacled lady in her forties, arrived with

some files. I was asked to fill a form, pay US$75, and got a visa

pasted on my passport. Task accomplished. The whole drama from

landing to passport stamp took 1 ½ hours. I walked into the

arrival lounge, and was warmly greeted by representatives of EcoTurNova

– Tanya who’s a qualified guide, Maxim the interpreter and Petre the driver.

Three individuals dealing with one chap. I felt like a VIP.

Foreign exchange goes a long way in this country. And so we set off

for Chisinau central.

|

|

|

|

|

Land of Wines and Confused Identities

"With regard to Southeastern

Europe attention is called by the Soviet side to its interest in Bessarabia.

The German side

declares its complete political

disinteredness in these areas."

Article III of the Secret Additional Protocol of the Nazi-Soviet Non Aggression Treaty

Moldova, also known to the rest of the world by its Russian name, Moldavia - is one of the three Romanian lands - the other two being Transylvania and Walachia. Moldova was first settled by the Dacian tribes more than 2000 years ago. The Romans came in the 1st century BC, conquered what were today the Romanian lands and intermarried with the Dacians. The Roman Empire withdrew in 275 AD but the Romanised heritage remained, to be merged with that of the various Slavic tribes that invaded this land. The result is a people whose language that still retains strong Latin elements though with some Slavic flavour, whose terminology resembles that of Italian, Spanish and Portuguese rather than of neighbouring ones like Ukrainian, Hungarian, Serbian and Bulgarian.

Empires rose and fell. Nomadic hordes came, burnt, raped, looted

and ebbed away with history. In Moldova, as in other Romanian lands,

peasant serfs toiled the land on behalf of the boyars, or landed aristocracy,

in times of peace. In times of war, they served in the boyars’ armies

fighting for causes they hardly understood. In 1359, in the face

of Hungarian and Turkish invasions, Bogdan of Cuhea united the Moldovan

principalities to form a united front against the enemies. In 1364,

the defeat of Hungarian forces solidified Moldovan independence.

Stefan cel Mare (Stephan the Great), 1457 – 1504, was Moldova’s greatest

voivod, or prince, who bravely defended the land against the Turkish, built

monumental painted churches and ramparts in what is today northeast Romania,

or Bukovina. Even then this golden age did not last, as Romania’s

enemies were simply too numerous and powerful. In 1600, the three

Romanian lands were briefly united under Michael the Brave, Prince of Walachia,

who took over Transylvania and Moldova as well. But even his glory

was short-lived, for in 1601, he was defeated and executed by the Habsburgs.

The first united Romanian state came to an end.

|

|

|

|

|

In 1812, the ever-expanding Russian Empire occupied the eastern half of Moldova and since then this eastern half (to be referred as Moldova in the rest of this travelogue) has a different destiny from the other parts of Romania. In 1918, after the Bolshevik Revolution, Bessarabia, as eastern Moldova was also known as, declared independence as the Democratic Moldovan Republic. This republic then joined Romania – for the first time since the era of Michael the Brave, the country was reunited again.

However, the new entity was not recognised by the new Soviet state. Stalin formed the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavia ASSR) in Transdniestria, the sliver of land east of the Dniestr River, where most of the inhabitants were ethnic Russians and Ukrainians. In 1940, in accordance to the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the USSR occupied Bessarabia and declared the territory the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (merging it with the Moldavian ASSR), and that the people here are not Romanians, but a separate semi-Slavic race called the Moldavians speaking a Slavic tongue called Moldavian. He forced the Moldovans to write in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet and adopted many Russian words in this artificially created language. The emigration of Russians, Ukrainians and other peoples from all over the USSR further enhanced the process of Russification. The Romanian language became the tongue of peasants while the urbanites spoke Russian at work and a Russo-Romanian pidgin at home.

This state of affairs lasted till Perestroika. The nationalistic Moldovan Popular Front was formed in 1989. The Latin alphabet was readopted in the same year and the “Moldovan Language” was declared the official language, much to the horror of the non-Romanian population. In fact, I have been told that in 1989, many people were afraid of speaking Russian in public. There was much talk of reunification with Romania, and ethnic minorities in the regions of Transdniestria and Gagauzia (where a Christian Turkish tribe live) declared their own republics in 1990. In 1991, with the collapse of the anti-Gorbachev coup, Moldova declared independence. Immediately, Transdniestria and Gagauzia rebelled. Transdniestria remains separate today, with a ceasefire in effect, but Gagauzia has chosen to reintegrate with Moldova as an autonomous republic.

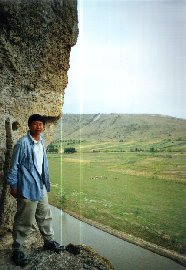

With

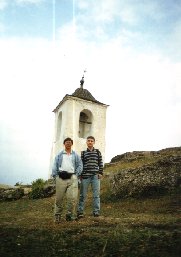

Maxim at the entrance of Old Orhei

With

Maxim at the entrance of Old Orhei

Years of independence have not brought prosperity. Newly independent Moldova has seen its national income dropped to less than a third of what it was in 1989, and on par with what it was in 1966. The country remains deeply divided, and perhaps even confused about its identity. The Constitution specifies that the national language is Moldovan, not Romanian, although for all intents and purposes, both are the same language. While some people still dream of unification with Romania, many wonder if unification with another poverty-stricken state would bring any benefits at all. Indeed, those early of days of nationalistic pursuits have led to rebellions and many deaths. Were all those sacrifices made in vain ?

Besides, the relative success of Russification also means that many

people remains more comfortable speaking Russian than Romanian, and more

familiar with the world of the FSU than that of Bucharest and Romania.

I have asked many Moldovans what they see themselves as, and I always get

a variety of replies, among them Moldovan, Moldavian, Romanian and even

“Roman”, whatever that is. Many Moldovans also have multi-ethnic

ancestry, e.g., a Russian grandmother, a Bulgarian father, etc. Some,

especially those from Transdniestria, remember the bad days of Romanian

occupation during the WWII, when troops of Antonescu, Dictator of Romania,

massacred many locals – Antonescu is today regarded as a hero in post-communist

Romania, to the horror of many in Moldova. The Moldovan state is

young. Only time will tell if an independent Moldova will last, or

whether a national identity will emerge. We mustn’t forget that when

Singapore became independent in 1965, nobody thought it would last beyond

a few years. Perhaps Moldova would prove cynics wrong.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trying to Launder Money In Chisinau

Chisinau, a city more well known by its Russian name, Kishinev, is Moldova’s graceful capital. First chronicled in 1420, Chisinau is laid out in a straight grid-like manner, with the most important government and commercial buildings along the four-kilometer long thoroughfare, Bulevardul Stefan cel Mare. Everything’s concentrated along Stefan cel Mare, from government ministries to hotels and department stores. In fact, most of the government ministries are located in a single huge block – someone told me that once you enter the main entrance, turn left for the Prime Minister’s Office, and right for the Ministry for Agriculture. “Too concentrated. Isn’t very healthy,” as a World Bank employee commented.

The sleepiness of the place and the huge Romanian signboards reminded me more of a Romanian provincial town than that of a FSU capital. Like Riga and Vilnius, Russian has disappeared from the public arena and in its place is a language that many do not know well. The next generation is being educated in the national tongue and perhaps their generation that will make the real linguistic switch.

I was driven to the National Hotel, also located along Stefan cel Mare

(what isn’t), where a room has been booked. Yet another old Intourist

hotel that has been taken over by the newly empowered governments and the

carpet smelled like some damp old book in your granduncle’s bookshelf.

Two Greek petroleum engineers on business and a Jewish-American in search

for ancestral roots were competing with me for the receptionists’ attention.

My turn came, and the receptionist had a look at my passport. “Singapur,

Kitai ?” Kitai is China in Russian.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Nyet. Republic of Singapore. Respublika.” I pointed at the national coat of arms on the passport cover. “Independent. Republic of Singapore, Asia.”

The receptionist nodded, “I understand. Everything OK now.”

She passed me the room key, my passport and the OVIR registration slip. I looked at the slip as I entered the lift. Country of Origin reads “Republic of Singapore, China.” I have given up. She must have imagined Singapore is a kind of SSR within an “Union of Republics of China” similar to the USSR.

I dumped my luggage in the room and was driven to EcoTurNova’s offices. For the purpose of securing the visa, I have earlier booked two nights of accommodation, a tour to Cricova, Moldova’s most famous wine cellars, and a first class overnight train journey to Kyiv. The money were wired to the firm’s bank account at a Moldovan bank, which, like many in the FSU, has an account with that infamous Bank of New York. Shortly after that, I got in touch with a kind chap from Gagauzia, who invited me to visit him and spent the night with his family. It was a wonderful opportunity to learn about Moldovan/Gagauz life and so I decided to cancel the second night at the National Hotel. I have also heard about how unsafe the first class trains are, and decided to take 2nd class (which some say is safer because the cabin is likely to be fully occupied) instead. Hence, I wanted a refund for the difference.

However, Moldovan laws does not allow the travel agency to refund me

the money (US$40 for the room and can’t remember how much for the train

ticket) without filling a hundred and one forms to certify that I wasn’t

involved in money laundering, gun-running and mafia activities, raping,

robbing, etc. Some time wasted in the discussion of alternatives

and phone calls were made to clarify regulatory issues involved.

Eventually I gave up. Let’s make things simple – In place of a refund,

I will take another tour – the one to Old Orhei, Moldova's most important

famous historical site.

Getting Drunk And Travel Back In Time

We drove out of Chisinau in light summer rain, into the lush green countryside of Moldova. This is a country with rich agricultural traditions, where wine accounts for half the export revenue. During Soviet days, its fertile black soil coupled with the policy of regional economic specialisation made Moldova the winery of the Union and Kishinev the chocolate candy manufacturer of the Union. The workers of Alma-Ata, Dushanbe, Moscow, Tashkent and Vladivostok had long relied on the fine wines of Moldavskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika to survive a life of shortages and stuffiness, as well as the long, harsh monotonous winters. Only that traitor Gorbachev, lackey of the West, as he is popularly known as to the people of the FSU these days, dare incur the wrath of the Working People, by forcing the closure of vineyards and wine bottling plants. Of course, he has been properly dealt with since.

Sunflowers fields, tobacco farms, vegetable plots, and vineyards.

We also passed a small patch of dense forest – Tanya said that’s part of

the Codru Forest. The Codru has a legendary place in the Moldovan

soul, a kind of Camelot and land of heroes. In times of troubles,

Moldovans have always sought refuge in its remoteness. When Stefan

cel Mare lost a major battle, he too, escaped to the depths of Codru, where

he rebuilt his army and went to battle with the Turks. Today, one

finds Codru a national brand name, adorning anything from wine and tobacco

to hotels and a premier league football team.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As we sped across the rolling hills towards Cricova, Tanya rattled off achievement statistics and data like a Soviet-era newsreader. I was more interested in chatting with Maxim, my bright young translator of partial Moldovan and Armenian ancestries. Merely eighteen years of age, he speaks good American-accent English, the result of a year in exchange programme in the United States. Cheerful and intelligent, he’s reasonably knowledgeable – I have met few on this trip who knows where Singapore is, or what we are good at. Maxim is curious about the world beyond, asking questions like “Why has Singapore prospered, while a much larger, resource-rich nation like Moldova remains poor?” He wants to be a journalist, possibly working for a Russian-language paper – another sign of the continuing influence of Russia and the Russian language ? But he also wants to live in America, the land of infinite opportunities and hope. And he too spoke about living in a Scottish castle, as what I couldn’t quite figure out. And of helping his beloved country develop. He reminded me of my younger days, so idealistic, cheerful and ambitious, and also full of mutually contradictory hopes and desires.

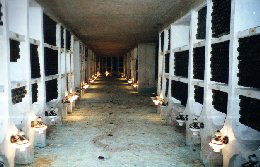

Fields. Cows. Fields. Cows. Fields. Cows. I struggled to keep myself awake in what soon became a monotonous landscape, given that I had only slept little more than four hours the night before. The Lada came to a screeching stop. We have reached Cricova, or rather, the entrance to the 60 kilometer-long underground cellars. These used to be mines – of what I can’t remember – but were converted into wine cellars when the minerals ran out. The deep underground cellars were linked together by impressive two lane sub-terran roads, with names like Sauvignon Blanc and Cabernet. In a country with few tourists, Cricova is Moldova’s most important tourist attraction, and one can only visit the cellars on a US$50 tour. Most visitors are UN diplomats and international aid workers stationed here. The lack of publicity, complicated archaic visa regulations, as well as plain inaccessibility prevent more people from coming.

We were brought around the cellars and shown the establishment’s impressive collection of foreign wines, some of which were part of Goering’s personal collection – I wonder how they landed up here – as Soviet war booty ? After the walk-around, we were brought to the elaborate wine-tasting halls. Another tourist awaits us – he’s a Danish journalist who told me he went to Transdniestria the day before. Not a problem, he says, you can get there without any border checks or special visas. The war had long ended and normality has returned, so much so that there are regular bus services between the Chisinau and the rebel statelet. I was encouraged. Must get there tomorrow, I thought.

We were given an introduction to the wine traditions of Moldova – for example, there is no minimum drinking age in Moldova, and customary birth rituals requires the wetting of the baby’s lips with some wine. They told me that Queen Elizabeth II takes Moldovan wine for breakfast everyday – a claim that was repeated by locals several times during this trip. But I told them I couldn't find Moldovan wines in Tesco and Sainsbury supermarkets. And indeed, few people in the UK have ever heard about Moldovan wines or even about Moldova the country – not to discount the quality of the Moldovan product but it was plainly clear that much publicity is needed. They also said they do export a fair bit to France. I am puzzled for the French are quite resistant to foreign wines. Perhaps, some French producers re-label them as French, and as ordinary table wines. We tasted 8 types of wines - you can imagine the after-effects – and was given a bottle of “Champagne” (labeled as Sparkling Wine) and a bottle of Cricova Cabernet to bring home. The wines tasted rich, although the Cabernet I brought home didn’t quite tasted like the same one I had at Cricova. Perhaps, they do have a consistency issue to sort out before they can export to the non-CIS world in a big way.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

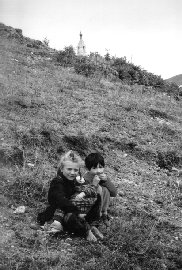

After Cricova, we set off for Old Orhei or Orheul Vechi, an amazing monastery located on a panoramic cliff-face in a strange round river basin. A prosperous city once stood in the basin, but was destroyed and rebuilt many times, by Mongols, Stefan cel Mare’s army and the Turks-Tatars. Today, the valley is but a lush green field, with corn, sunflowers, vegetables, etc. It was the late afternoon when we arrived in Orheul Vechi, and the gradually dying sun was carving deep cut shadows in the hills. We went straight to the Monastery and a caretaker opened the doors – she was of relatively dark complexion. My companions said that the people in the countryside are the “pure” Romanians, whereas urbanites like them tend to have elements of Ukrainian, Russian, Bulgarian, Jewish and what-have-you blood, and so appear fairer. Anyway, we were brought around the smallish church virtually carved out of the rock. From the cliff-side of the monastery, one could see the River Raut meandering lazily around this basin of fields, while playful kids were having fun with their cows and sheep along the riverbanks.

The village next door was a journey into 18th century Moldova – hardly any machinery was seen. Old men on their donkey carts. A dark robed Orthodox priest clearing a pile of hay. An elderly wrinkled lady in traditional dress getting water from those elaborate ornamental wells typical of the Moldovan rural scene. The smell of the earth heavy in the air. A shoeless child and his cow. It was exhilarating. I was flown into a Moldova of another age, into the pages of a Leo Tolstoy work, a poem by Alexander Pushkin. No wonder Tanya called this place a village God has forgotten.

![]() 9

SEPTEMBER: TIRASPOL, TRANSDNIESTRIA: Arrested in a Rebel Republic

9

SEPTEMBER: TIRASPOL, TRANSDNIESTRIA: Arrested in a Rebel Republic

| RETURN TO FROM THE BALTIC TO THE BLACK SEA HOMEPAGE |